Some of the more important properties are:

- Sector size at offset 30

- Short sector size at offset 32

- Total Sector Allocation Table (SAT) sectors at offset 44

- Sector ID of of first sector used by Directory at offset 48

- Minimum size of a standard stream in bytes at offset 56

- Sector ID of the first sector used for the Short Sector Allocation Table (SSAT) at offset 60

- Total sectors used for SSAT at offset 64

- First part of Master Sector Allocation Table (MSAT) starts at offset 76

To get the actual number of bytes used for a sector and short sector, raise two to the power of each size. For example, if sector size is 9, then the sector size in bytes is 2 to the 9th power, or 512, bytes. If short sector size is 6, then the short sector size in bytes is 64.

Once you know the sector size (ignore the small sectors for now), you can now divide the OLE CF file into chunks that are each the "sector size in bytes" bytes long. Each of these is a sector.

One thing to keep in mind is that sector numbers are relative vs. absolute offsets. To calculate an absolute offset to sector data, we have to take our sector number, multiply it by the sector size, and then add 512 bytes for the header to it. This will come up a lot later.

This concept will work in a somewhat similar way for small sector storage as well, but in the small sector storage case, once we have the bytes that make up the small storage space (more on this later), the small sector number is in fact absolute from the start of the bytes that make up the small storage. We could of course just calculate things in a similar manner as above (header size + absolute offset to small storage + (small sector size * small sector #) but its easier to visualize if you think of small storage as its own little island of data (at least for me it is).

The next thing to understand is the minimum size of a standard stream value. In most cases this value is 4096. This threshold determines whether things stored in the OLE CF file will be kept in primary storage or in small storage. The reason for this is primarily one of storage efficiency. If you are storing a bunch of small things then, it is a waste to store them in increments of 512 bytes when you only need 87 bytes.

SAT AND SSAT

Next, lets talk about the SAT and SSAT. Both work in essentially the same way in that they track which sectors or small sectors are part of a run of data, are free, etc.

Think of both of these structures as an array where each slot contains a number. This number can indicate a few things but typically the number in each slot will indicate the next slot to go to, an end of run indicator (-2), or an indicator that the record is free (-1)

To build the SAT and SSAT, we first have to look at the Master Sector Allocation Table (MSAT). As indicated above, the MSAT (up to the first 109 parts anyways) is stored in the header starting at offset 76. At this offset is a run of 109 32-bit (4 byte) signed integers that point to the sectors that we need to read to build the SAT and SSAT.

As a simple illustration, suppose we had data as seen below starting at offset 76:

00 00 00 00 == 0 decimal

80 00 00 00 == 128 decimal

00 01 00 00 == 256 decimal

80 01 00 00

00 02 00 00

80 02 00 00

00 03 00 00

80 03 00 00

00 04 00 00

80 04 00 00 == 1152 decimal

00 05 00 00 == 1536 decimal

80 05 00 00

00 06 00 00

80 06 00 00

00 07 00 00 == 1792 decimal

FF FF FF FF == -1 decimal

These values correspond to the relative sectors where the data that makes up the SAT can be found. Now all we have to do is go to each position as specified in the MSAT (until we see -1 as that indicates its free), gather the data, and concatenate it together with what came before it. Once we do this we will have our Sector Allocation Table.

An example

Let's look at an example for a few of them to make things more clear.

In order to find the absolute offset, we apply the formula we saw earlier.

The first one is easy.

(0 * 512) + 512 = 512 or 0x200

If we look at offset 0x200 in a hex editor we see the following:

![]()

As another example, if we look at the second entry, we can calculate it as follows:

(128 * 512) + 512 = 66048 decimal, or 0x10200

If we look at that offset in a hex editor we see the following

![]()

Once we do this for all the sectors we can now find the data that belongs to things that are stored in the SAT (remember, this is anything bigger than 4096 bytes).

If we look at the first chunk of data above for our SAT, we see the following (grouped in 4 byte chunks):

FD FF FF FF == -3 decimal

08 00 00 00 == 8 decimal

15 00 00 00 == 21 decimal

04 00 00 00 == 4 decimal

05 00 00 00 == 5 decimal

06 00 00 00 == 6 decimal

07 00 00 00 == 7 decimal

09 00 00 00 == 9 decimal

12 00 00 00 == 18 decimal

0A 00 00 00 == 10 decimal

and so on.

if we visualize this in a different way, like this:

![]()

we can start making sense of things a bit better.

The first entry in each sector that makes up the SAT has a special signature, FD FF FF FF, which is -3 in decimal. If you build out a SAT that came from more than one sector you will see this signature in it. Since each sector is 512 bytes and each sector ID is 32 bits long, that means we get 128 sector IDs out of one sector. Based on this you should see -3 every 128 entries in the SAT. Moreover, since we know this signature will always be the first entry in a SAT sector, we can check for it when we go to an absolute offset. If we see -3, we know we are in the right place. If not, the math is off.

Recall that one of the important header fields is the sector ID of where our Directory starts (we will cover exactly what the Directory is later). In our header above, this is found at offset 0x30, which is 1 in this case. Based on this, we can start building our data run for where sectors that hold our Directory live.

As we did with the SAT, we need to go to each sector in the run, get some data, and concatenate it together. Once that is done, all of the Directory entries can be processed (again, we will get to this later).

So in our SAT above, if we look at slot 1, we see an 8. Next we go to slot 8 and we see an 18, next we would go to slot 18 and see what number is there. We continue to do this until we get to a slot with a -2 in it as -2 indicates the end of the data run.

So, for the bytes that make up the Directory, we repeat our process as we saw above:

Start with sector 1, which is (1 * 512) + 512 = 1024 (0x400) bytes from offset 0. Looking there, we see:

![]()

Slot 1 points to slot 8, so we calculate again:

(8 * 512) + 512 = 4608 (0x1200)

Looking there, we see this:

![]()

And so on for all the sectors in the run that makes up the directory.

You may already be able to see a pattern in there, but if not, don't worry, we will discuss the Directory soon. The important thing to grasp here is how we find our data run and then go get the bytes that make up whatever it is we are interested in.

Break time

Whew! That was a lot of information! Go get a cup of coffee. Don't worry, I'll wait.

Back to it

Now that we have the SAT out of the way and we understand how we get the bytes for a particular structure, we can now talk about the SSAT. The SSAT works exactly the same way as the SAT did in that it is way for us to look up our data runs for things stored in short storage. Not every OLE CF file has a SSAT, so you have to check if the sector ID for the first SSAT sector is greater than 0. If there isn't a SSAT, the sector ID will be -2.

To get the bytes that make up the SSAT, we follow the data run, just like we did for the directory. Once we do this we will get another list of things like we did for the SAT (think slot 0, slot 1, slot 2, etc).

In our example above, the SSAT first sector is at offset 0x3C. In the header above, this value is 640 decimal, or 0x280. Again we do the math and we get: (640 * 512) + 512 = 328192 or 0x50200

Looking at this offset we see:

![]()

This is now works the same as we saw when building our SAT. The difference between the SAT and SSAT tho is where we go to get the data. Before we talk about that however, we need to talk about the Directory.

Directory

The Directory is made up of directory entries, each 128 bytes long. A directory entry contains such things as a name, a type, a creation and modification time, a sector ID of the first sector that contains the data for the directory entry, and the size of the directory entry in bytes.

The Directory is basically a catalog of all of the objects which are stored in an OLE CF file. Recall earlier that we built out our directory bytes by using the SAT. The first part of the Directory bytes looked like this:

Since each directory entry is 128 bytes long, let's dissect one

![]()

So the following is true about this directory entry:

Name: Root Entry

Name length: 22 (includes terminator)

Type: 05 (5 denotes root storage, but other common ones are 1 for storage, 2 for stream, etc)

Created on: (creation date not stored)

Modified on: 02/22/2016 18:09:43

First sector ID: 3

Size: 611136 bytes

This process is repeated for every 128 bytes that we find in the bytes that make up the Directory object.

Root Entry is special

In the above example, we can see the name is Root Entry and the size is 611,136 bytes. The root entry is a special directory entry in that the bytes in the Root Entry are the bytes used when we have to get data for an object stored via the SSAT. In other words, all objects smaller than 4096 bytes will end up being in the Root Entry object. In jump lists, this means pretty much all lnk files will be found inside the Root Entry bytes.

If you think of the SAT corresponding to the entire jump list file, the SSAT corresponds to just the bytes that correspond to the Root Entry data. In this case, the size of the data for the Root Entry is greater than 4096 bytes, so we need to use the SAT to get the data. Once we have that data, we can cut it up into 64 byte chunks and index each of these chunks starting at 0.

From there we can, as needed, get the bytes for things stored in the SSAT by building data runs from the SSAT and then going to the bytes referenced by the Root Entry (the 611,136 bytes previously discussed). As each 64 byte chunk is found according to the data run, it is concatenated together. When we are done we will have the bytes (and possibly some slack) for a stored object. To determine the bytes that make up the logical "file" we use the size of the Directory entry. Anything beyond that size, up to the end of the bytes that were concatenated together, would be considered slack.

So now that we have seen how the core concepts of the SAT, SSAT, and the Directory work, we now have the means to find blobs of data (and the type, timestamps, etc.) that lives inside an OLE CF file.

Cool!

There is one other special directory entry, the DestList, that we will talk about next.

DestList

If we extract the bytes as indicated by the directory entry named DestList, we get something that looks like this:

The DestList directory entry contains a 32-byte header followed by DestList entries which are of variable size.

The header contains things like:

- Version number

- Number of DestList entries

- Number of pinned DestList entries

- Last entry number used

and each DestList entry contains things like:

- Volume Droid ID

- File Droid ID

- Birth volume Droid ID

- Birth file Droid ID

- Hostname

- Entry number

- Last modified timestamp

- Pin status

- Path size

- Path

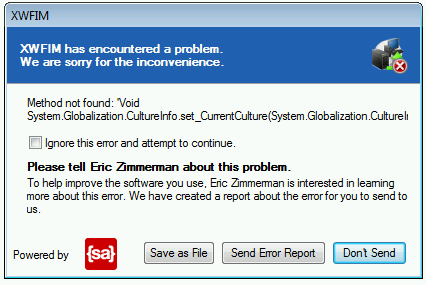

Jump lists prior to Windows 10 used a version number of 1, but in Windows 10 (which RTM'ed on July 15, 2015), this version number is now 3. This is because the structure of a DestList entry has changed and this in turn broke just about every tool that can parse jump lists. This may range from crashing to displaying only part of what is in a DestList and silently dropping the rest.

I have been running Windows 10 since its release and as such, started using Windows 10 jump lists for my testing. When I got to DestList parsing, my code was failing after implementing the working specifications I linked to earlier (Metz stuff).

I then did some Googling and found

one reference to Windows 10 and a change in jump list format:

In this post, ssenyl documented the changes he saw and after coding my parser I can confirm his conclusions based on the data I have available in my unit tests.

The difference between the two formats is not drastic, but it is enough. In version 1, the path is found at offset 114 and in version 3, it is at offset 130.

But where are the lnk files?

Ah, I am glad you asked! Recall the Directory is like a catalog of everything stored in the jump list. Each lnk file that is referenced by a DestList entry is stored as an item in the Directory and has all the same info (Name, start sector, etc) we saw when we initially discussed the Directory. To get the bytes that actually make up a lnk file, we simply check the size of the lnk, then use either the SAT or the SSAT to build our data run and gather the bytes we need.

Putting it all together

Forgoing all the nasty stuff going on under the hood, when processing automatic destinations jump lists, things boil down to the following:

1. Process all Directory entries

2. Find DestList

3. Process DestList entries

4. For each DestList entry, find the corresponding Directory entry where DestListEntry.EntryNumber == DirectoryEntry.Name

5. Once we have the Directory entry for the lnk file, we can go get the bytes that make up the lnk file.

6. Display DestList info and dump information about lnk file

Step 5 is the important one, so let's look at that a bit closer.

Below we have a DestList entry with entry number 1112, or 0x458.

Next, we need to look for the Directory Entry with a Directory Name of 458. When we find it, we see it looks like this:

Now that we have our Directory entry got the lnk file, we now know how big the Directory entry is (864 bytes) and that we need to use the SSAT to go get the data because the size is less than 4096.

So if we use the SSAT to build our data run, gather our data, and write it out to a file named, for example, 458.lnk, it would look like this:

If we look at the properties for this file, we can see the size, which matches what we expected from the Directory entry:

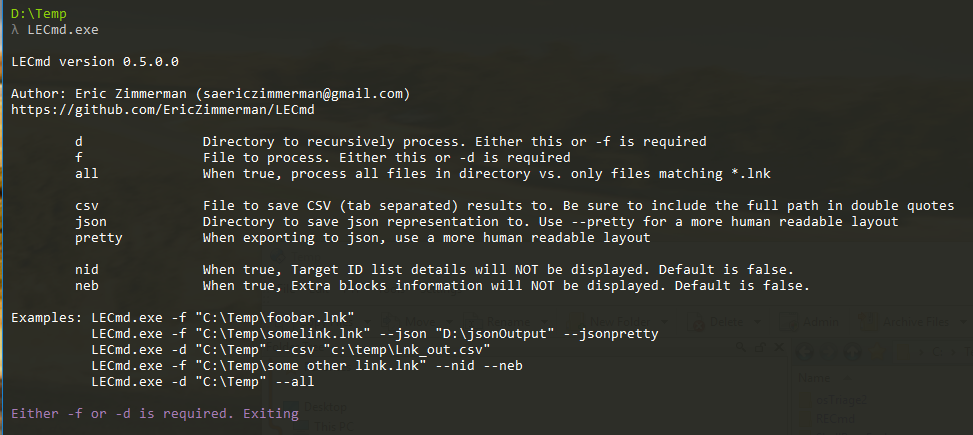

and finally, if we process the file using LECmd, we can see all the details:

Now we just do that hundreds of times in a few seconds and you have the contents of jump lists at your disposal!

Some tool testing

Note: If anyone has any other tools known to work (or not work) for Windows 10 jump lists, please let me know and I can update the post. I know as of X-Ways Forensics 18.8 preview 3 that Windows 10 auto dest jump lists are parsed properly. Here is the partial output of the jump list we have been discussing in X-Ways:

![]()

The Total property above is the value of the Last entry number from the DestList header.

Here is an example of the amount of data that is available in the auto dest jump list we have been discussing.

The following objects are what my OLE CF project builds when parsing an automatic destination jump list.

Notice the number of DestList entries in X-Ways matches what I have calculated (673) and this matches what is in the DestList header

![]()

You can see DestList has 673 entries and DirectoryItems has 675. In this example, there is one Directory entry for each DestList. The two extra Directory entries are Root Entry and DestList.

The above screen shot is from Visual Studio debugging my OLE CF parser. If we expand the DestList entries collection, we see this:

![]()

Here I have two of the 673 DestList entries expanded, but you can see the detail in there.

Notice the first entry (0) references a path that contains "DarkCometInformation.txt", the second (1) references "Internet.pdf", and that both of these are referenced in the partial X-Ways output as well.

For the rest of the discussion, keep in mind there are 673 DestList entries in this particular auto dest file.

Here is what one very popular tool (according to the Twitterverse) outputs when parsing this same jump list:

![]()

Only the first DestList item is displayed.

Here's the output from another popular tool:

![]()

With this example you can clearly tell something is wrong.

Here is another tool that tells us there is a problem:

![]()

And another:

And another that indicates an issue:

![]()

And another:

![]()

Who cares?

Well, Windows 10 has been out for a long time now and with Microsoft's push to get to a billion installations continually ramping up, examiners will start seeing more and more Windows 10 boxes.

This is where things like unit testing come into play (we have come full circle now!). If a Windows 10 auto dest jump list was added to a suite of unit tests soon after Windows 10 was available, the issue would have manifested itself immediately and could have been corrected much sooner.

In my testing I do things like this:

![]()

That last line says if the number of DestList entries does not equal the number of entries as reported in the header, the test should fail. You can see by the green dot it does not fail and I have test cases with over 700 DestList entries in them from Windows 10.

Wrapping up

You still here? Wow! I am impressed! I barely made it myself. I hope this post has made it a bit more clear how jump lists work and the importance of automated testing via unit tests.

The next tool I will be releasing is my jump list (custom and automatic) parsing tool, JLECmd, which will handle Windows 7 thru Windows 10 jump lists. It will be open source and available on GitHub after the initial release.

Output will be similar to the detail you get in LECmd in regard to the embedded lnk files with the additional DestList entry details added on.

Here is a preview:

It will (eventually) allow you to export all free space found in the SAT and SSAT, dump all lnk files out to a directory (this is what I posted about on Twitter,

here), and more.

I will have some other surprises too at some point that will make new research into jump lists a lot easier which I hope the community uses to its benefit.

Bye for now!